By A Special Correspondent

First publised on 2025-12-08 15:12:35

A section of the media today claimed that scientists may have found a 'cure' for male-pattern baldness in an acne drug approved five years ago. The drug in question is Clascoterone, a topical anti-androgen currently sold for acne under the brand name Winlevi. The claim is not baseless. But calling it a 'cure' is, at best, premature.

Clascoterone is a topical androgen-receptor blocker. In simple terms, it prevents male hormones like dihydrotestosterone, or DHT, from activating oil glands and hair follicles in the skin. This is why it works for hormonal acne - it cuts off the hormonal trigger locally, without significantly altering hormone levels in the bloodstream. Until recently, Clascoterone was strictly an acne medication. It is approved only as a topical cream, not as a tablet or solution, and only for acne treatment.

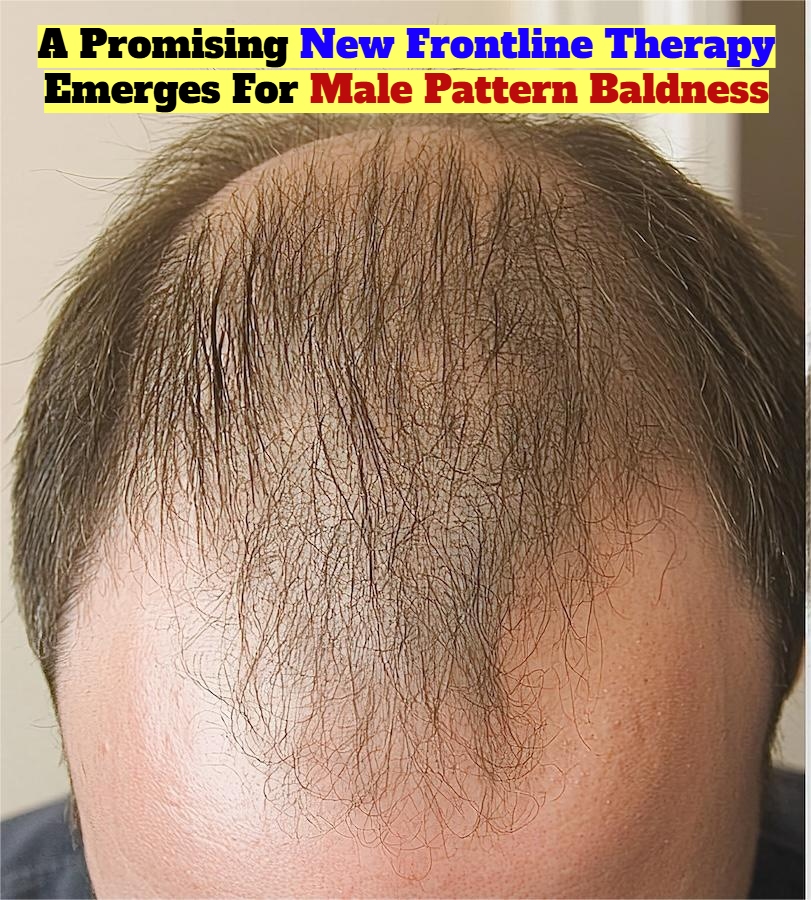

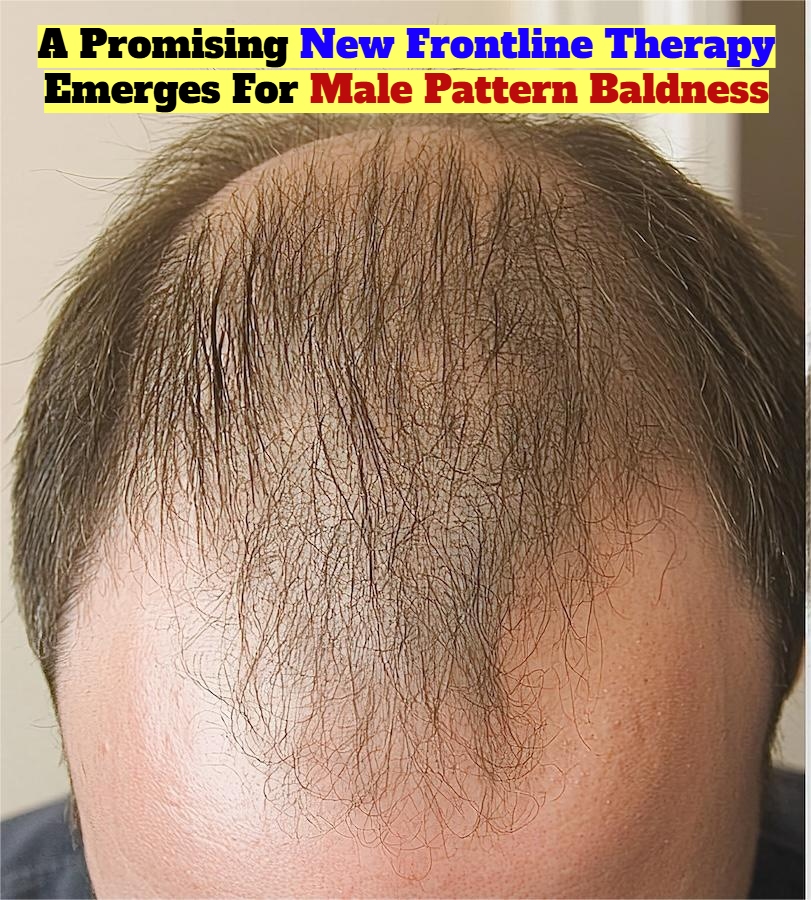

Male-pattern baldness, or androgenetic alopecia, is also driven by DHT acting on genetically sensitive hair follicles. This biological overlap explains why scientists began exploring whether Clascoterone's anti-DHT action could be repurposed for scalp hair. That possibility moved closer to reality in late 2025, when Cosmo Pharmaceuticals announced positive results from two large Phase-III clinical trials of a Clascoterone 5 percent topical scalp solution for male-pattern baldness. According to the company's data, one trial showed up to a five-fold higher hair growth in the target scalp area compared to placebo, while the second trial reported a lower but still statistically significant improvement. The safety profile was reported to be close to placebo.

This is the scientific basis on which today's headlines rest. What the headlines do not emphasise is just as important. Clascoterone is not yet approved for hair loss anywhere in the world. The acne formulation is not the version used in these baldness trials. Those studies used a 5 percent scalp solution that is still awaiting regulatory clearance. The trials ran for only about six months, and there is no long-term data yet on whether regrown hair is maintained after stopping treatment, whether the effect plateaus over time, or whether delayed side-effects emerge. Dramatic phrases like "five times better than placebo" reflect relative improvement and do not necessarily translate into full cosmetic restoration. A large percentage jump can still mean a modest visible change, depending on how much hair loss a patient already has.

This is why the treatment must be viewed as a promising new frontline therapy, not a proven cure. Current gold-standard treatments work through different mechanisms. Minoxidil improves blood flow and prolongs the growth phase of hair, while Finasteride reduces DHT levels systemically. Clascoterone, if approved for hair loss, would become the first truly local anti-androgen scalp therapy, targeting DHT at the follicle without altering blood hormone levels. This could make it safer for men wary of sexual or mood-related side-effects linked to oral anti-androgens. But safer does not automatically mean more powerful.

For Indian patients, the practical reality is straightforward. Clascoterone is not approved for hair loss in India. The acne version is not officially marketed for baldness treatment. Any off-label or imported use would be unregulated and medically risky. Even if global approval comes through in 2025 or 2026, Indian regulatory clearance would still take time.

Clascoterone represents a real scientific advance in the fight against androgen-driven hair loss. It may soon join, or even partly replace, existing treatments for men who cannot tolerate oral anti-androgens. But calling it a "cure for baldness" today is scientifically inaccurate and medically irresponsible. Baldness remains a chronic, hormone-driven condition. New tools can slow it, reverse parts of it, and cosmetically improve it - but the word "cure" still does not belong in this conversation.